Last night I got an email from Los Angeles that made me whoop. Turns out I was right to trust my gut. To reach out to him.

It all goes back to last summer when I was stopped in my tracks by a song I heard on Gilles Peterson’s Radio 6 show.

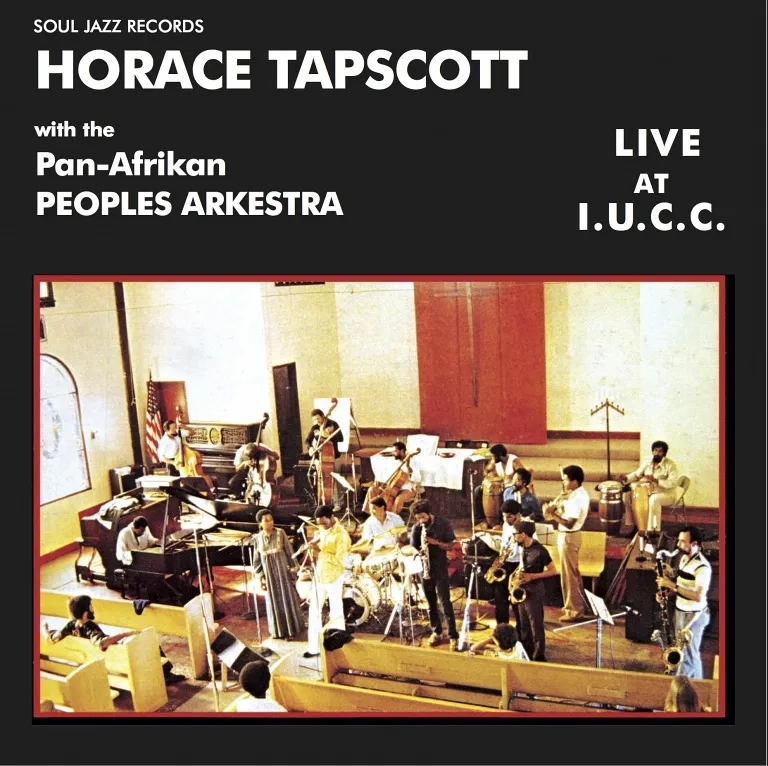

‘McKowsky’s First Fifth’ was a sprawling, 15-minute jazz odyssey recorded in a church on 85th and Holmes in L.A. in 1979 by Horace Tapscott and the Pan-Afrikan People’s Arkestra.

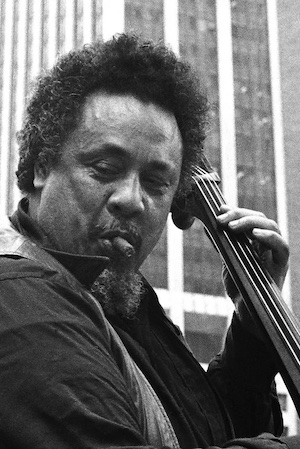

As well as a pretty weird name, the track had piano runs, flights of flutes and soprano sax. It had stabs of tuba and trombone slides and cascades of clarinet. But that wasn’t what grabbed me.

Rising above all of this curated wonder and chaos was a voice that carried itself like a staff into battle. His words landing like seeds falling, bedding into the earth, bursting into flowers. Into flame.

It was a voice so matured through time that it had become timeless. Rooted in communion with things unseen.

For the first time since I was a kid, I wrote all the words out, listening again and again to catch the cadences. Writing and crossing out and rewriting. Arranging it in verses and stanzas until it hung just right on the page. The page, a leaf dripping honeydew.

“The world is a whole note, sustained, augmented and diminished by divinity.”

I bought Horace Tapscott with the Pan-Afrikan People’s Arkestra live at IUCC to discover the name of the poet whose words had seized me. I wanted to reach out to him, to ask if I could plant his spoken word into a track I was working on; harness his power and bring it to an audience who might have forgotten what passion sounds like and how devotion can soar.

But the track didn’t appear on this album.

I was crushed. I did some more digging, ordered a few more LPs. Hell, I even got the cell number of Jesse Sharps, the man credited with writing the song, but couldn’t get through to him. It’s fair to say that at this point that I was on a mission. I’d become obsessed.

But shortly after that I gave up. Maybe the name of the spoken word artist was never recorded, lost in the annals of time. Maybe I would never find him. Maybe he had passed on to the next world, was ‘standing on the cosmic stage now.’

By night then, I gently lifted his voice from the track and arranged my music around it, like ivy curling around anthracite. It was released on September 6th as track 7 on my debut. The track is called ‘The Western Ways are Dying’; a line taken from ‘McKowsky’s First Fifth’

And then, and I can’t remember how, a few weeks ago, I came across an album called ‘Healing Suite’ by LA-based collective, The Gathering, released in 2022.

‘Healer from the depth of us come

Healer from the depth of us come

Mender of minds

Soother of souls’

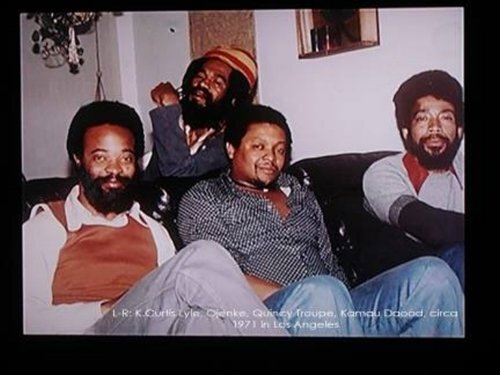

These words ascribed to the performance poet and mythic figure in the Southern California arts scene, Kamau Daáood. Was it the same voice, the power, performance and lyricism of the voice that shook the air (and me) in that recording over 40yrs ago?

Back to the digging and googling and chatgpt-ing. A few prospective emails turned up nothing, some bounced back, other mailboxes were full.

And then last night this came and in and I dissolved into a fanboy swoon.

“Eden. I understand you been trying to reach me. Let me know what’s on your mind. Hope all is well.

Brightness

Kamau”

Kamau Daáood was raised in Watts, an LA neighbourhood pivotal to the civil rights movement. James Brown name checked Watts in his music, as did NWA and Kendrick Lamar. The place is a symbol of resilience, resistance, and the complex interplay between oppression and hope. And to me, Kamau and his words represented all of this. He was the source. Not to mention the fact that his poetry readings have brought him to podiums with the likes of Gil Scott Heron and The Last Poets.

And here he was. In my inbox.

Holy fuck.

I messaged back. Was it him reciting his poetry in that 1979 recording? (Yes) Did I have his blessing to use and credit his voice on the my track ‘The Western Ways are Dying’? He replied…

“I like what you’ve done with the track. Recorded over 40yrs ago. You have my blessing to use it, giving it new life…I realize that these projects are a labour of love first and foremost.”

It was this last line that got me.

“These projects are a labour of love first and foremost.”

It meant he’d got me.

And I’d been right about him too.

That a man, now in his seventies, who’d devoted his life to raising up his community and giving a voice to the viciously disenfranchised, would not be primarily concerned with copyright and royalties. Not, at least, if he sensed that behind the request was a man toiling in love’s name. Whose songs were, first and foremost, a labour of love.

I’ve made some poor choices in my life.

Reaching out to Kamau was not one of them.

0 Replies to “The western ways are dying”