The conversation between Aunty Mary and Nigel has turned to trees.

Aunty Mary can name the whereabouts of every Monkey Puzzle tree from here to Abergavenny and up and down the Honndhu valley. There’s something sinister, we agree about Monkey Puzzles, and aloof too. I talk about the colossal Yew trees in the churchyard of St Mary’s Chapel, their trunks as wide as industrial dustbins, streaked and woebegone with age.

Apparently, in the old days, every family had to plant a Yew in front of their gardens, something to do with protection, I think. Aunty Mary and Nigel talk about a neighbour whose Yew recently died from the inside out (I know the feeling). A relative delivered a brand new one to his door but he failed to plant it and it died on his doorstep. There is some consternation about all this.

As they talk, my mind begins to wander, tuning to the vibe in the house.

Three generations of women live here; Aunty Mary at the top of the tree, her daughter, Jessica who looks after the trekking business together with her daughters, two energetic women in their twenties, who look after the Air BnB bit.

The place is grounded in memory and ancestry, unified through the generations who have ploughed their furrows here; this is not the nuclear family I grew up in.

The sense of reach and expansiveness touches and calms me, my tribal, ancestral brain soothed by the tendrils of connection that snake out from this kitchen and over the valley.

I feel deeply at home in a home that is not my own; held and ballasted by the inter-generational web of familial weight and connection.

This feeling deepens over a breakfast of bacon butty and double-fried eggs the following day.

I’d like to come back.

In the old days in India, at a certain age, children would be sent off to the local ashram to begin their education. They would lodge there for many years, slowly woven into the web of community roles and relations. It was known as the Gurukula system and brought about a maturing and transformation in the child, nurtured in a fine and diaphanous web of belonging.

This was the model that underpinned the yoga teacher training I attended in India at the turn of this century. Aspiring yogis (we were over 100-strong) living cheek-by-jowl in an ashram; eating, shitting, sleeping and learning asana, pranayama, yoga philosophy and some pretty eye watering cleansing techniques (apparently, the reason the water we were given to drink tasted so God-awful was that it was infused with iodine to calm our sexual arousal).

Of all the very many things I learned, one has stayed with me and still makes me think…about education and healing and community.

It was the notion, mentioned towards the end of the course, that all of the stuff we were learning (how to cleanse your digestive tracy by swallowing a piece of string, the Bhagavad Gita’s most exalted chapters, how to wipe your bum with your hand alone) were just vehicles for transformation, secondary methods at best.

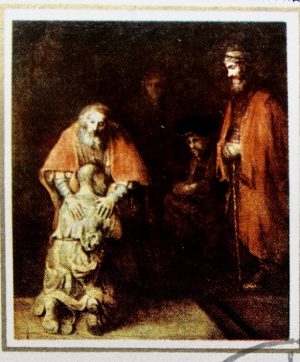

That the real transformation occurred in the teacher-pupil relationship that the environment fostered. And that all of the knowledge and learning was a means by which the pupil could deepen their connection to the teacher. That maturing, the shedding of old skins were the fruits of relationship, were relational, rather than what we conventionally think of as learning and education.

That blew my mind.

Because it meant to me that the Buddha, with all his exhortations to solitude and self-inquiry had missed the mark.

And it convinced me that I had to go back to the Grange.

0 Replies to “OVER THE GOSPEL PASS (5/5)”